Bath Abbey’s collection of monuments is on a par with those in Westminster Abbey, and its wall tablets and ledgerstones outnumber those in Westminster. Dr Oliver Taylor, Bath Abbey’s Head of Interpretation and Engagement, has written a book about the monuments – here are some selected excerpts.

There are 635 tablets on the walls of Bath Abbey… The ones that have attracted comment have traditionally been those by celebrated sculptors whose work has commemorated celebrities of local or national life. But the Abbey’s monuments are not simply monuments to those whose rank or income meant they were buried in Bath rather than Westminster Abbey. True, Bath Abbey contains monuments to some who might have been buried and commemorated in Westminster. However, Bath Abbey’s monuments are also uniquely a collection through which can be read the story of the parish church building itself and the rise of Bath as a spa. They are a sorely underappreciated aspect of the city’s famous Georgian heyday.

The Royal Crescent, Circus, Baths, Pump Room, and Assembly Rooms are rightly appreciated as the places frequented by Bath’s fashionable 18th-century visitors. However, the Abbey, as the church attended by those visitors, is rarely mentioned, and nowhere is it addressed that during the Georgian period the Abbey was a ‘gallery of sculpture’ that attracted numerous visitors and citizens who wanted to admire the latest works of art by artists working in a serious and respected artform: the English church monument. Certainly monuments to the first rank of politicians, admirals, doctors, philosophers, bishops, soldiers, merchants and others can be found. But so too can those of Bath’s teachers, socialites, cloth merchants, poulterers, booksellers, mayors, sculptors, plumbers and publicans, to name but a few. Hidden in the lines of their monuments is an unwritten social history of Bath.

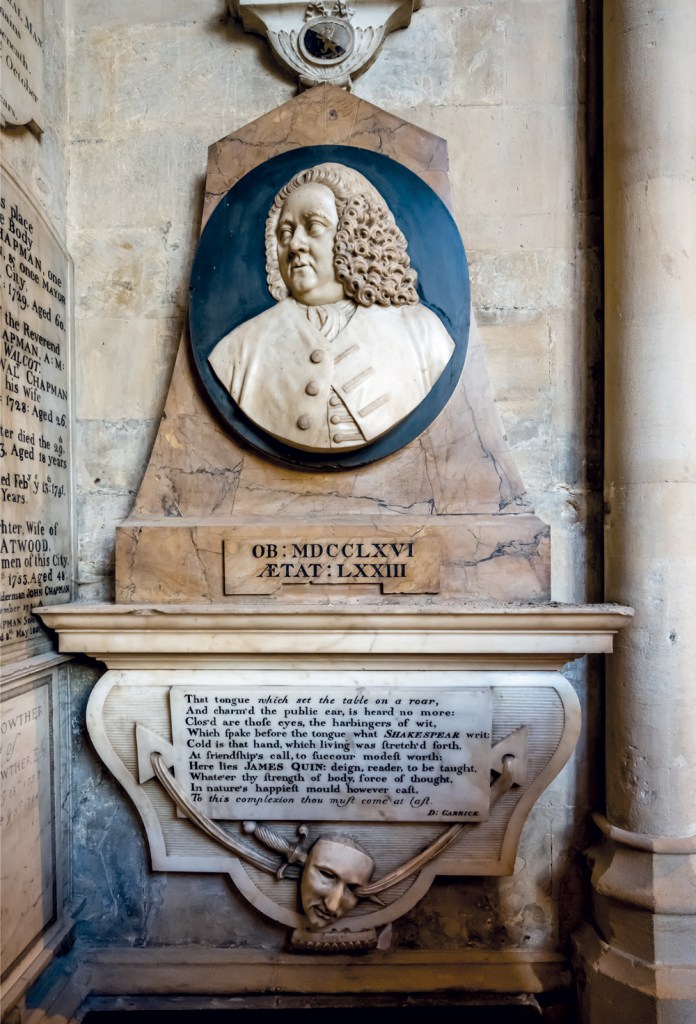

James Quin’s monument

James Quin was ‘privately interred in the Abbey on 25 January 1766. His tablet was erected three years later on ‘a pillar at the south-eastern end of the nave”.

The 1778 survey describes it as follows: “On the pyramid of Sienna marble is a medallion of Namur black marble, with a striking Likeness of the deceased, and Cyprus branches on each side; underneath is a sarcophagus, of statuary marble, on which is a table, with an epitaph wrote by Mr Garrick, under which is a mask and a dagger, representing Tragedy and Comedy.”

Until now, writers have largely reduced thinking on the Abbey’s monuments to two quotable but questionable phrases conceived in the early 19th century. Henry Harington’s description of the Abbey: ‘These ancient walls, with many a mouldering bust, / But show how well Bath waters lay the dust’ – and John Britton’s statement that ‘Perhaps there is not a Church in England, not excepting that national mausoleum, Westminster Abbey, so crowded with sepulchral memorials.’

Britton was right to identify Bath Abbey’s monuments as on a par with those in Westminster Abbey in 1825. Bath Abbey’s over 1,500 monuments are a nationally significant collection. Bath’s 635 wall tablets are comparable in number with the ‘just over 600 tombs and other substantial monuments’ in Westminster Abbey. Add to that number Bath Abbey’s 891 ledgerstones (flat inscribed gravestones), almost three times as many as the ‘more than 300 memorial stones and stained glass windows’ at Westminster, and one could easily correct Britton’s statement to say that Bath Abbey has the largest collection of monuments of any church in England.

However, the combination of the English church monument’s fall out of fashion in the mid-19th century and the extent of the alterations to Bath Abbey’s monuments in the 1830s and 1860s has led them to be all but forgotten. A fact all the more surprising given their importance in Georgian Bath. Whilst the Abbey’s spectacular medieval architecture, rather than its monuments, contributes to the Outstanding Universal Value of the UNESCO World Heritage City of Bath, the importance of the Abbey’s monuments is acknowledged three times in Historic England’s Grade I listing of Bath Abbey. The ‘exceptionally high concentration of memorial tablets (some 640 in all) from the C17 onwards attests to the church’s central place in Bath society’.

This book tells the story of the monuments. How did a ruined Tudor abbey come to have the largest collection of church monuments in the country by 1845? How has this collection been seen by those who have visited the Abbey, and how has it been cared for and added to by the generations who have looked after the Abbey?

What do we encounter today when we look around the Abbey, walk across its floor, and read the monuments? This book argues that the monuments played an important role in the rebuilding of the Abbey as a parish church in the late 16th and 17th centuries, helped to create a new identity for it in the 18th and 19th centuries, and that what we encounter of them today is the result of major renovation and conservation work in the 19th and 21 centuries, respectively. All illustrative of the way in which the Abbey has invited, benefited from, cared for, and managed its monuments for over 400 years.

Bath Abbey’s Monuments by Dr Oliver Taylor (The History Press), £22, is published on 17 August.